Celebrated author Judith Barrington knows how to tell a story. A poet and memoirist, her work has won numerous awards in the United States and overseas. She teaches creative writing at the collegiate level.

The memoir is such a powerful medium for telling one’s story. You’re a masterful storyteller. How did you wind up entering the genre?

I was a poet first — and still am. But sometimes I found I was writing something that was narrative and the story element begged to be in prose and wanted to be longer than most of my poems. At first I simply tried writing short memoirs and included one in each of my first two poetry collections. Then, later, I started to teach memoir and thought a lot about the genre. As I did that, my memoirs grew longer until I was writing novella-length pieces and then a full-length book, Lifesaving: A Memoir.

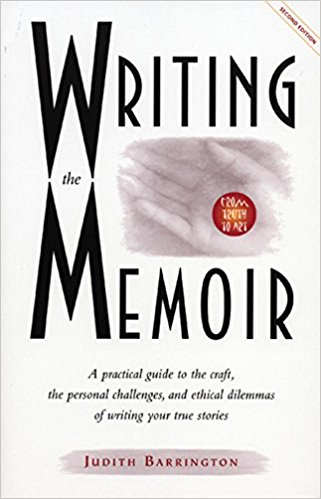

An international bestseller, Writing the Memoir has helped thousands of writers. When were you inspired to begin crafting it?

After I’d taught several classes on the memoir genre. Each time, I figured out another issue that I could address in the class, and found examples from literary memoirs. This forced me to read a lot of this kind of writing, both current and from the past, and to figure out the roots of this new wave of personal writing. This was perhaps in the early 1990s.

Magnificent memoirs don’t come together by themselves. What makes one worth assembling and reading?

I’d first think of the element of lovely writing. No matter how tough the subject matter, it can be made palatable and engrossing by a style that is rhythmic, imagistic, varied, and well-placed. A magnificent memoir has many elements common to poetry.

Second, I think the writer must be ready to tell that story. S/he cannot be still immersed in the feelings such as being hurt or angry, or needing revenge. To be ready, the writer will have done sufficient work and introspection so that the storytelling is an end in itself, with no need to coerce the reader into taking sides.

Third, the story cannot have been told over and over. Or, at least, if it has been, the writer must ask new questions about it, including “Why have I told this story so many times?” A new layer of meaning must emerge.

The best memoirists live “an examined life” (all the time).

An award-winning memoirist and teacher, you’ve heard every excuse, from writer’s block to time management. Young or inexperienced writers undoubtedly at times struggle. Besides reading your bestselling book, how should an aspiring memoirist respond?

In my teaching experience, writers who lack time, feel blocked, or have reasons NOT to tell their story (e.g. someone in the story must die first; a sibling will disagree; a child be hurt, etc., etc.) are looking for ways to undermine the project. This is not willful but often self-protection. Protecting the people in the story or simply not having enough time often more likely means protecting oneself from getting close to painful material. Most memoirs demand honesty about painful experiences. This is usually the explanation for superficial problems like time management, even though time may truly be an issue. Using time well may in the end require giving up something to make room for regular writing.

Since the late-twentieth century memoirs have risen in popularity. What’s the reason?

There have been many theories. I think one ingredient is the kind of fiction that has become popular – shorter than Charles Dickens or T.S. Eliot, far fewer characters, and “postmodern” sensibility. Another is the kind of lives most of us live now — lives that do not make room for us to tell each other stories of our lives. No sitting around the fire sharing childhoods; no communal solving of lifelong dilemmas. Another ingredient must surely be the growth of comfort (in the USA) with telling personal stories: the increase of the therapeutic society.

Of people with whom you’ve worked, which are most memorable? Why?

Adrienne Rich because she exhorted me to give up trying to be entertaining, but rather to dig deeper and be more honest. Her own readings exemplified this quality.

Mimi Khalvati (UK) whose poetry and speech are pure music and who understands poetic craft brilliantly.

Maxine Kumin because her work meticulously blends formal elements with autobiography.

You write poetry too. What about this form of expression has seduced you?

Poetry was my first love. I was seduced by the need to find the perfect word — not just for meaning, though that is important, but also for sound and image. I loved playing with forms – both traditional and contemporary as well as free verse. I liked learning to be a better performer of my work. Nowadays I like finding out what I feel and think because a poem talks back to me even before I know exactly what it’s saying.

Learn more about Judith Barrington:

- JudithBarrington.com homepage

- Poets & Writers profile

- WOW! Women On Writing – “Twenty Questions Answered by Judith Barrington”

- Quotes on GoodReads.com

- Soapstone.org – “Celebrating Women Writers”

Check out two of her books:

Ms. Barrington is bestselling author of Writing the Memoir and Lifesaving.

Enjoy learning from gifted writers? Read our interview with nine-time New York Times bestselling author Peter Golenbock.