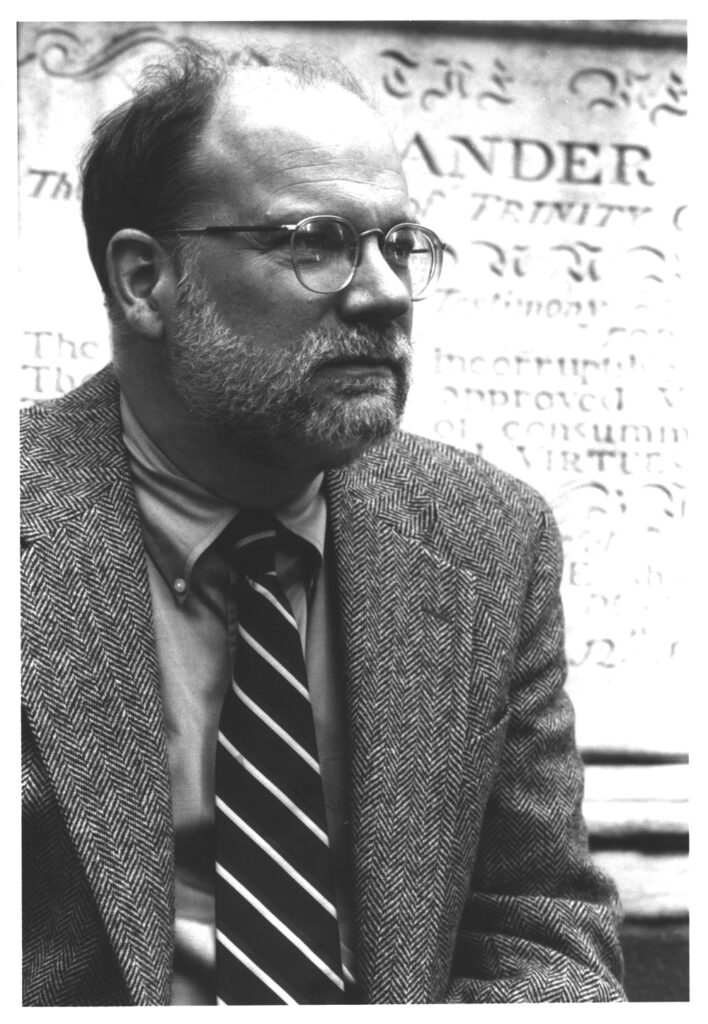

The life of John Steele Gordon – finance historian by trade, global adventure-seeker by nature – would enthrall even the dullest mind. An Oscar Wilde quote that appears on his homepage reads, “The one duty we owe to history is to rewrite it.” He describes stimulating foreign journeys, the stock exchange, and a couple of history’s best-kept secrets.

Following a six-year post-college stint at a publishing company, you set out on a nine-month Land Rover quest from New York all the way down to Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. What prompted this 39,000-mile trek?

That was in 1972-73. In 1970 I had driven from London, U.K., to India and back (that trip would be no fun at all today) with a professional touring company. The next year I drove all around México. I looked at a map and figured out that the furthest point I could drive to from New York was Tierra del Fuego and so I went. I’m afraid wanderlust is a family disease. I’ve been as far north as Anchorage, Alaska, as far south as Tierra del Fuego, as far east as New Delhi and as far west as Hong Kong. And there are lots more world to see.

World travel is in your blood. Which makes for an ideal exploration?

That depends on what you are looking for. I’d love to drive across Africa, but I’m too old for that now, alas. I’ve never seen South Africa. Europe is full of history. If I haven’t been there I want to go and if I liked it the first time I want to go again.

When did you know that covering U.S. financial history was your professional destiny?

I had been working as New York City press secretary for U.S. Representative Herman Badillo but there wasn’t much to do as most of the work was done in D.C. So I started going to the New York Public Library (NYPL) and writing stories such as the sinking of the General Slocum. I wanted to write one about the gold panic of 1869, probably the most exciting day in the history of Wall Street. I knew a lot of Wall Street history as my grandfather was a broker and had seen a lot of it himself (he was active on the Street from 1898 to 1974). I knew what selling short was before I could ride a bicycle. So I went to NYPL to look up what books had been written about the Erie Wars, of which the gold panic had been a part. I was astonished to discover that the most recent book had been written in 1871 while the wars were still going on. So I decided to write that book myself. It was published in 1988. The editor at American Heritage read it, noticed that I had included a short essay on the historical problem of comparing monetary sums over time (what would $100 in 1866 money be worth today?). They had tried several times to find someone to write that piece, so they hired me, ran it on the cover, asked me to be the Business of America column writer and the rest, as they say, is history. In other words, I fell into it.

An author of books on Wall Street and the national debt, you are well-versed in consumer behavior. Are Americans practicing responsible spending and saving habits?

I think most American families, unless poor, are reasonably dealing with money. The ones who aren’t are called public officials and I fear there is a terrible reckoning coming in that regard. The first thing to do is to take away from elected officials the power to determine how the books are kept. Wall Street forced business to adopt Generally Accepted Accounting Principles at the turn of the 20th century, and we need to force government to do the same. Woefully underfunded public pensions, spiraling national debt for no good reason (unless getting re-elected is a good reason) etc. etc.

What’s your approach to writing consistently? Is inspiration ever an issue?

Well, inspiration never hurts, but it comes most easily when you’re trying hard. Having an editor yelling at you to finish doesn’t hurt either. Also, of course, hunger. Sometimes a story possibility just jumps out at you.

Your Barron’s articles resurrect significant, though relatively mysterious, names, e.g. 1300s Mali emperor Musa Keita I – “the richest man who ever lived” – and Italian mathematician Fibonacci. How are said subjects chosen?

Musa Keita is very obscure to westerners and I saw his name in a Forbes article that peaked my interest. It’s really impossible to compare money over 700 years and two very different civilizations, but it was fun to speculate. Being interested in mathematics, I’ve known about Fibonacci for a long time. But I hadn’t realized that he had, in effect, grown up in his father’s counting house and thus realized the practical value of Arabic numerals – they can help you make money! – rather than just making mathematical calculations easier. I also welcomed the excuse to write about so-called Russian multiplication.

“To use Russian [or, properly, ancient Egyptian] multiplication, place the numbers to be multiplied side by side. Then, below the first number, halve it repeatedly, ignoring remainders, until you get to one. Below the second number, double it the same number of times. Then, if the number on the left is even, cross out the corresponding number on the right. Add up the remaining numbers on the right, and you have the answer.”

–John Steele Gordon, “The Man Behind Modern Math”

The secret of writing short articles – which are much more time consuming on a per-word basis than longer things like books – is to keep several balls in the air at once, such as Arabic numerals and Russian multiplication, to entertain the reader as well as inform him. Like all forms of creativity, I think an artist doesn’t really know how he does it; he just knows when he’s done it.

Learn more about John Steele Gordon

- JohnSteeleGordon.com

- C-SPAN video appearances

- American Heritage articles

- Barron’s articles

- Commentary Magazine author archive

- Imprimis article “Entrepreneurship in American History”

- Freakonomics guest post “Greed, Stupidity, Delusion — and Some More Greed”

- Twitter.com/SteeleGordon

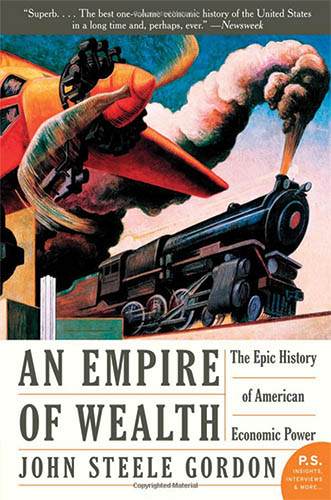

Read John Steele Gordon’s books

- An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Economic Power

- A Thread Across the Ocean: The Heroic Story of the Transatlantic Cable

- Hamilton’s Blessing: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Our National Debt

- The Great Game: The Emergence of Wall Street as a World Power 1653-2000

- Washington’s Monument: And the Fascinating History of the Obelisk

- The Business of America: Tales from the Marketplace – American Enterprise from the Settling of New England to the Breakup of AT&T

- The Scarlet Woman of Wall Street: Jay Gould, Jim Fisk, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the Erie Railway Wars

- Overlanding: How to Explore the World on Four Wheels

Mr. Gordon is a columnist at Commentary Magazine and Wall Street Journal contributor.

Can’t get enough economics? Meet Lawrence Reed of the Foundation for Economic Education and Nobel Laureate Vernon Smith.

Enjoy envious travel stories? Jump right into these interviews with master marketer Marcia Yudkin and bestselling author James Moore.