Dr. Jacques Bailly serves as chief pronouncer of the Scripps National Spelling Bee, which he won as a fourteen-year-old competitor in 1980. If you’ve watched televised final rounds any time since 2003, then you’ve seen and heard him. For us, the college professor was kind enough to answer five questions on his own studying strategies, lifelong learning, and philosophy.

In 1980 you won the National Spelling Bee. Mastery of any craft requires hours of practice. What was your middle-school study schedule?

That was 36-38 years ago [from late 2016], so it’s a bit hazy. I was involved in spelling bees for three years (6th-8th grade), starting out in the Fall of the first year with about an hour a week as a group (the spelling club), which intensified a bit in the Spring. Did that for two years, but became much more serious the second year. After the archdiocesan qualifying bee, the spelling club would be reduced to just a few of us, and we’d study more. But basically, we were trying to memorize “Words of the Champions,” a list of about 3000 words published by the Scripps-Howard National Spelling Bee (now the Scripps National Spelling Bee). In the third year, I became much more serious. I studied perhaps 3 hours a day all Spring, and after I won the Colorado-Wyoming spelling bee, I just studied words as much as I could.

What are your recommendations for youngsters looking to partake in competitive bees? Can parents, siblings, mentors help?

For my money, your best bet is to memorize the few hundred words in Spellit. Just do that as a memorization task. From there, make sure you are taking a foreign language if you can. More than one is better. Look at that language and look at how it spells words: this is all about recognizing patterns, in English and elsewhere, that can help you. Look at where words came from (almost all words have a previous version, whether it is an older English version or English borrowed it from another language or made it up from available word elements). Part of this is learning spelling, but most of it is just patterns: how words work, including spelling, meaning, history, etc. Find patterns. Then, find the exceptions to the patterns. Make lists of words (don’t worry if the same word appears on more than one list). Quiz yourself. Above all, have that kind of fun that only happens when you lose yourself in an activity and look up and realize that, good grief, it’s already dinner time.

After graduating from Brown University and learning German through a Fulbright scholarship, you proactively reached out to the Scripps National Spelling Bee organizers, lending your assistance. Why did you write this letter?

Well, just on a hunch that maybe I had the skills that they might need. I knew French, German, Greek, Latin, and a little Arabic then. I also had a lot of participation in spelling bees under my belt, and I had watched and helped my mother coach another national champion speller (Molly Dieveney, our neighbor at the time) and several other spellers. My mom and I talked endlessly about spelling bees and words: after a while, my mother knew how to coach spellers so much better than I had ever been coached, and she really loved doing that. So, I knew spelling and spelling bees and the most relevant languages for hard words in English. I lucked out in that the spelling bee just happened to need a new associate pronouncer (the fact checker for the pronouncer and, in extremis, back up pronouncer).

How would you describe your growth as a lifelong student and college professor?

Of course. I am proud to say that I now have enough credits to be a midyear sophomore at the University of Vermont [UVM], where I teach Greek and Latin: I’ve taken computer science, math, Chinese, French, and more. Of course, I already had a degree from Brown, and another from Cornell, but why stop. Maybe someday I will complete my UVM degree, but I don’t have a major yet.

With an inquiring mind, if you are not learning, you are dying: I live to learn and thereby learn to live. It’s all part of a big huge web of tangled and interconnected endeavors shared with millions of people.

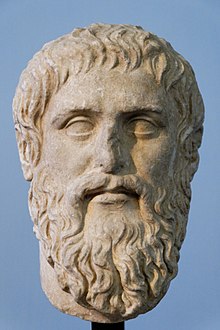

Your doctoral dissertation was on the dialogue Theages. You teach Greek, Latin, Plato, Aristotle, and etymology courses. You’re also Graduate Coordinator for the UVM Classics department. Ancient philosophy provides, in your words, “a way to approach questions that matter.” Please elucidate (not to be confused with your winning word, elucubrate!) your adoration of classic texts, languages, and thinkers.

Here’s why I love classics: almost any discipline of human thought has roots in Greece. Chemistry, math, history, literature, theatre, philosophy, geology, biology, meteorology, logic, etc. (the list could go on for a long time). All of them can be traced back to Greece. Some can be traced back further, and some arose also elsewhere, but the Greeks transformed whatever they touched: I don’t know why, but there was something rational in the air in 6thc. BCE Greece and later Greece. They not only had the guts to try to explain the world without magical divine influence, for instance, but they believed the crazy theories they came up with. They wrote them down. They wrote down things like everything is earth, air, fire, and water, OR everything is atoms and void, OR everything has the seed of every other thing within it, OR everything is just one thing, unchanging, unchangeable, with no past, present, or future, and then later thinkers built upon them. I cannot figure out why they did that, or why other cultures don’t seem to have done that so much, unless they somehow tapped into that Greek heritage.

Basically, I’m a child of enlightenment rational thought: I believe we have made progress and can make more, and I believe that our progress has to do with knowledge and learning. I’ve delved into the past. Others push into the future, invent things, discover scientific principles and laws, etc. There are many of us pushing humans to be better and do better and think better, some by teaching, some by doing, some by just working hard, but all by learning. I don’t think Plato or Aristotle got it right (I do like the stoics, however), but they got us on a path that just might lead us to get it right someday. When they were wrong, it is almost laughable to us today, but we can only get the little we get right because someone came before us to show us the way. The past is fascinating in itself, but also for the light it can shine on the now or the future.

Learn more about Jacques Bailly

- Wikipedia entry

- TIME Magazine Q&A

- USA Today article – “Meet the most interesting man at the National Spelling Bee”

- USA Today article – “He’s read every word since 2003 until this year. Meet the voice of the Scripps Spelling Bee.”

- Sporting News article – “Who is Dr. Jacques Bailly? Meet the Scripps National Spelling Bee’s longtime pronouncer”

- IMDb profile

- University of Vermont faculty page

- Academic résumé

- Curriculum vitae

- Commentaries on Latin letters

Watch and listen to Dr. Bailly pronounce words during the Scripps National Spelling Bee final rounds on ESPN every spring.

Do you enjoy getting to know interesting academics? Read our interviews with Edmund Burke scholar Ian Crowe, economist Gary Wolfram, historian Burt Folsom, and number-one-bestselling author Larry Schweikart.